Islamic Mosaic Art

Islamic architecture used mosaic technique to decorate religious buildings and palaces after the Muslim conquests of the eastern provinces of the Byzantine Empire. In Syria and Egypt the Arabs were influenced by the great tradition of Roman and Early Christian mosaic art. During the Umayyad Dynasty mosaic making remained a flourishing art form in Islamic culture and it is continued in the art of Zellige and Azulejo in various parts of the Arab world, although tile was to become the main Islamic form of wall decoration.

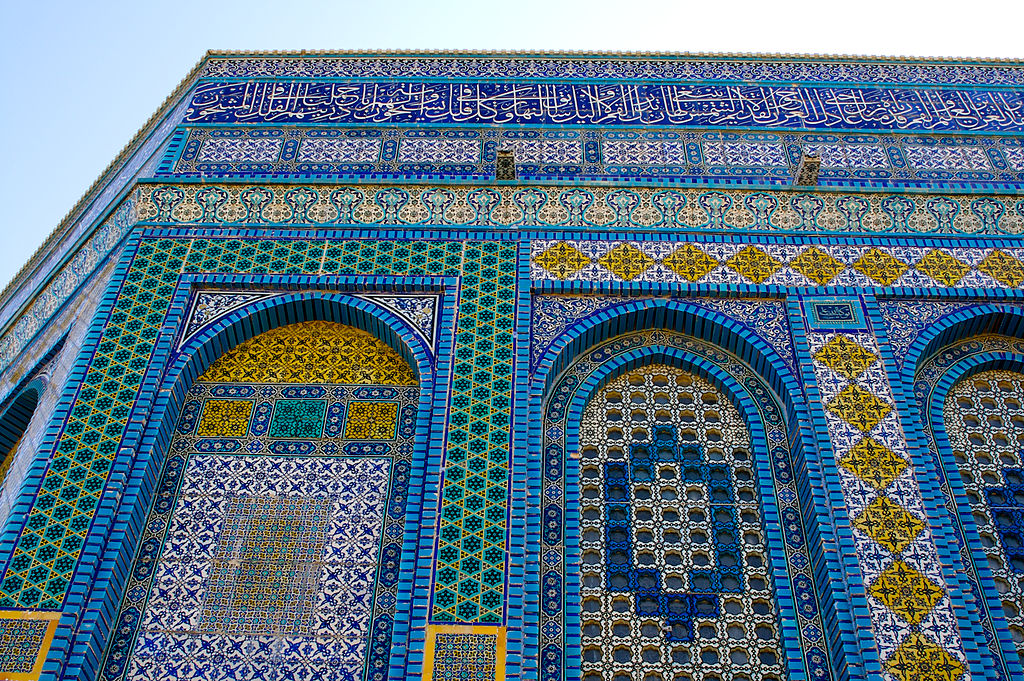

Islamic Mosaics Inside the Dome of the Rock in Palestine (c. 690)

The first great religious building of Islam, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, which was built between c. 688-692, was decorated with glass mosaics both inside and on the outside, by craftsmen of the Byzantine tradition. Only parts of the original interior decoration survive. The rich floral motifs follow Byzantine traditions, and are "Islamic only in the sense that the vocabulary is syncretic and does not include representation of men or animals."[1]

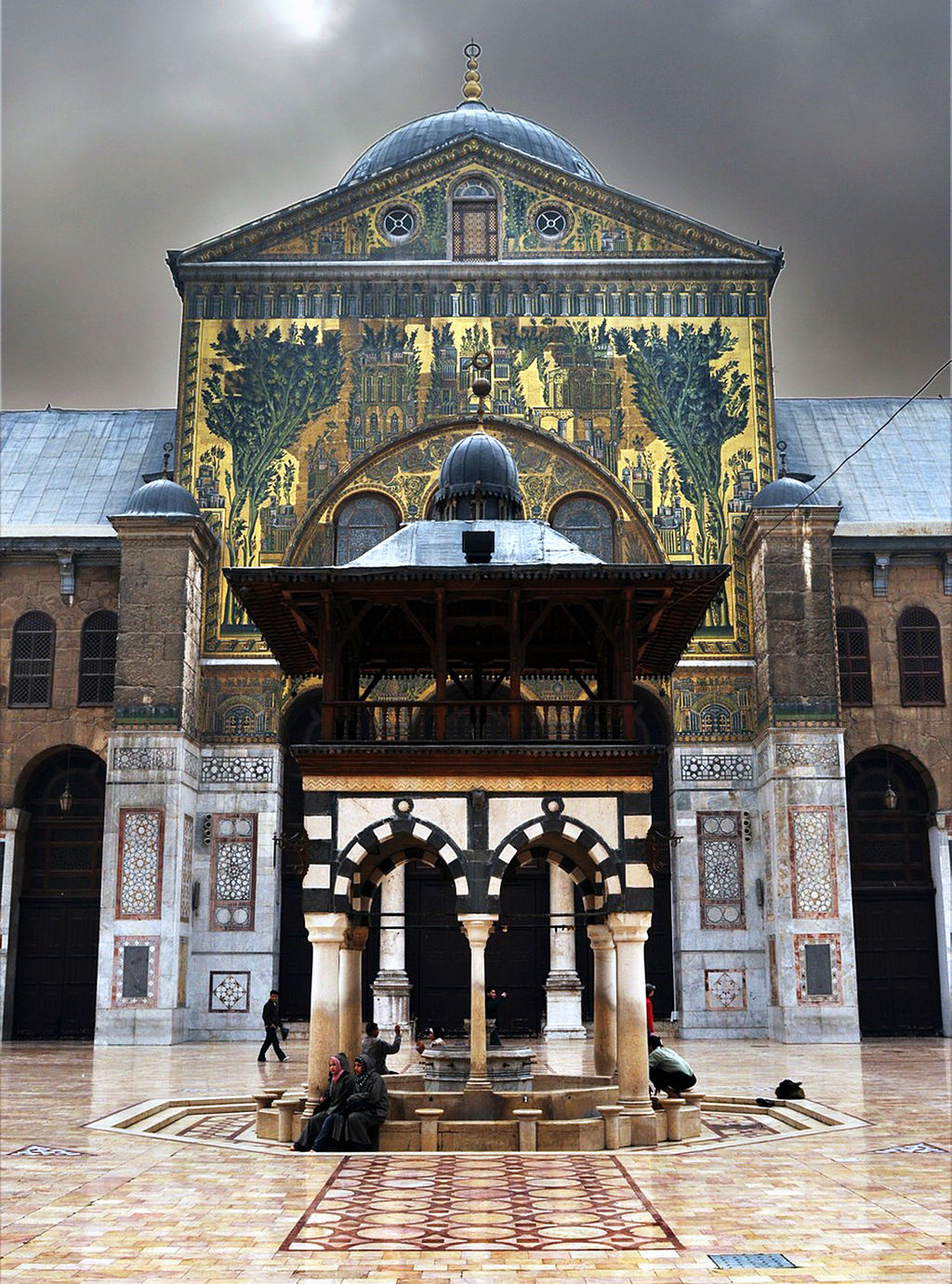

The Umayyad mosaics of Hisham's Palace closely followed classical traditions. The most important early Islamic mosaic work is the decoration of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, the then capital of the Arab Caliphate. The mosque was built between c. 706 and 715. The caliph obtained 200 skilled workers from the Byzantine Emperor to decorate the building. This is evidenced by the partly Byzantine style of the decoration. The mosaics of the inner courtyard depict Paradise with beautiful trees, flowers and small hill towns and villages in the background. The mosaics include no human figures, which makes them different from the otherwise similar contemporary Byzantine works. The biggest continuous section survives under the western arcade of the courtyard, called the "Barada Panel" after the river Barada. It is thought that the mosque used to have the largest gold mosaic in the world, at over 4 m2. In 1893, a fire damaged the mosque extensively, and many mosaics were lost, although some have been restored since.

The mosaics of the Umayyad Mosque gave inspiration to later Damascene mosaic works. The Dome of the Treasury, which stands in the mosque courtyard, is covered with fine mosaics, probably dating from 13th or 14th century restoration work.

Their style is strikingly similar to the Barada Panel. The mausoleum of Sultan Baibars, Madrassa Zahiriyah, which was built after 1277, is also decorated with a band of golden floral and architectural mosaics, running around inside the main prayer hall.[2][3]

Classical Geometric Motifs in Umayyad Mosaics

Non-religious Umayyad mosaic works were mainly floor panels which decorated the palaces of the caliphs and other high-ranking officials. They were closely modeled after the mosaics of the Roman country villas, once common in the Eastern Mediterranean. The most superb example can be found in the bath house of Hisham's Palace, Palestine which was made around c. 744. The main panel depicts a large tree and underneath it a lion attacking a deer (right side) and two deers peacefully grazing (left side). The panel probably represents good and bad governance. Mosaics with classical geometric motifs survived in the bath area of the 8th-century Umayyad palace complex in Anjar, Lebanon.

The luxurious desert residence of Al-Walid II in Qasr al-Hallabat (in present-day Jordan) was also decorated with floor mosaics that show a high level of technical skill. The best preserved panel at Hallabat is divided by a Tree of Life flanked by "good" animals on one side and "bad" animals on the other. Among the Hallabat representations are vine scrolls, grapes, pomegranates, oryx, wolves, hares, a leopard, pairs of partridges, fish, bulls, ostriches, rabbits, rams, goats, lions and a snake. At Qastal, near Amman, excavations in 2000 uncovered the earliest known Umayyad mosaics in present-day Jordan, dating probably from the caliphate of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (c. 685-705). They cover much of the floor of a finely decorated building that probably served as the palace of a local governor. The Qastal mosaics depict geometrical patterns, trees, animals, fruits and rosettes. Except for the open courtyard, entrance and staircases, the floors of the entire palace were covered in mosaics.[4]

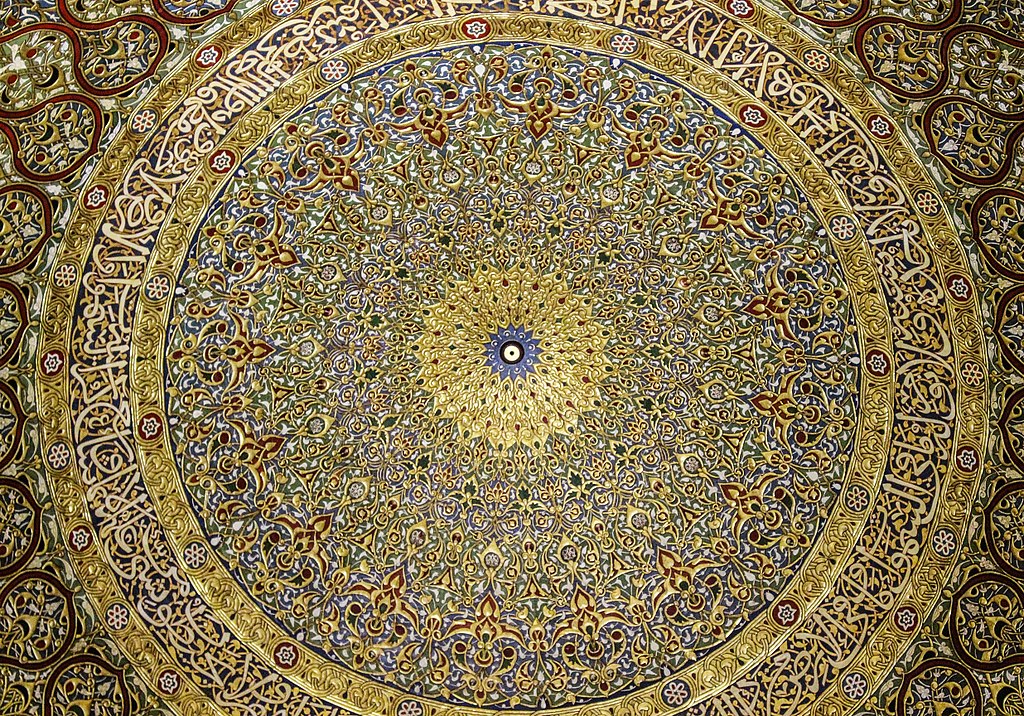

Golden Mosaics in the Dome of the Great Mosque in Cordoba (c. 965-970)

Some of the best examples of later Islamic mosaics were produced in Moorish Spain. The golden mosaics in the mihrab and the central dome of the Great Mosque in Cordoba have a decidedly Byzantine character. They were made between 965 and 970 by local craftsmen, supervised by a master mosaicist from Constantinople, who was sent by the Byzantine Emperor to the Umayyad Caliph of Spain. The decoration is composed of colorful floral arabesques and wide bands of Arab calligraphy. The mosaics were purported to evoke the glamour of the Great Mosque in Damascus, which was lost for the Umayyad family.[5]

Mosaics generally went out of fashion in the Islamic world after the 8th century. Similar effects were achieved by the use of painted tilework, either geometric with small tiles, sometimes called mosaic, like the zillij of North Africa, or larger tiles painted with parts of a large decorative scheme (Qashani) in Persia, Turkey and further east.

Sources

1. Kuban D. Muslim Religious Architecture. Leiden: E.J. Brill; 1974:28.

2. Al-Zahiriyah Library. Enwikipediaorg. 2018. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Zahiriyah_Library. Accessed April 24, 2018.

3. Madrasa al-Zahiriyya | Archnet. Archnetorg. 2018. Available at: https://archnet.org/sites/1854. Accessed April 24, 2018.

4. Al-Yousef G. Floor Mosaic. Discoverislamicartorg. 2018. Available at: http://www.discoverislamicart.org/database_item.php?id=object;ISL;jo;Mus01_H;17;en. Accessed April 24, 2018.

5. Dodds J. The Great Mosque of Cordoba | Briefing | Professor Jerrilynn Dodds | Medieval Architecture. Learncolumbiaedu. 2018. Available at: http://www.learn.columbia.edu/ma/htm/dj_islam/ma_dji_discuss_cordoba.htm. Accessed April 24, 2018.